In early April, Congress approved a small business relief fund of $376 billion. When that amount proved inadequate, they offered an additional $310 billion. Today, the Biden Administration is again seeking additional funding to keep small businesses afloat. While this was a powerful gesture on Congress’s part to support the many small businesses across the country, the program itself has definitely had issues. Most notably, the program ended up funding businesses many wouldn’t even classify as small. Much of the businesses’ funding was used to pay government fines, buy out other companies, or simply pad the executives’ pay.

Moving away from the fund itself, the terms of the loans seem pretty reasonable. Most of these loans have terms of just one percent interest rate, while others won’t have to repay the loan at all (usually under the condition of keeping all employees on payroll). Under normal circumstances, these terms would be more than enough to keep businesses afloat. Unfortunately, as we all know, these are not normal times. While small businesses are guaranteed six months of forbearance under the package, the loan will still come due. How will a business owner afford to make these loan payments? Even once social distancing protocols are relaxed, the economy will be slow to move forward.

In 1982, I began my career as a Federal Banking Regulator for the Farm Credit System, just as the US agriculture sector crashed. As the economic devastation spread to the rest of the economy, I was transferred to general debt restructuring and liquidations. Debt restructuring is the process of reassigning more favorable rates and terms to a debt based on the premise that the bank would lose less money.

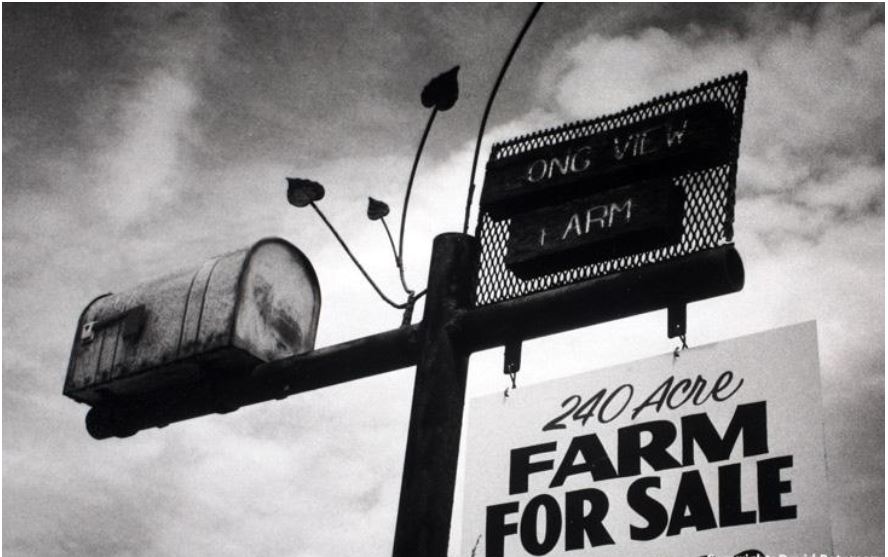

The Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) was authorized to issue billions of dollars in low-interest loans to assist the farmers with their massive financial losses. At first, the farmers were appreciative of the financial support. However, as time passed by, the farm income did not return to the pre-crash levels, not even close. In fact, for nearly a decade, year after year, the government issued bailout after bailout to keep the farmers in business. In the end, the financial demise of agriculture can, in part, be attributed to those “low-interest loans.” Then, like now, the probability of incomes returning to their pre-crash levels is not likely. In the end, the farmers did not receive enough in price increases to enable them to make those payments, and over time that debt ballooned.

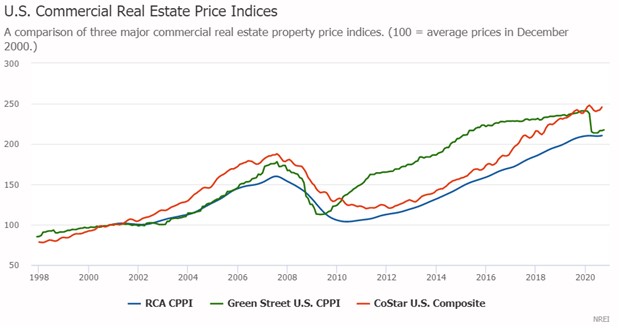

Today, since the Great Recession of 2008, real estate of all types have skyrocketed in values and rents. For example, Cap rates have been at historically low levels for the last 5-7 years. In 2019, according to Real Capital Analytics’ Commercial Property prices are nearly 30 percent higher than their 2007 peak. Multifamily properties have outpaced other sectors, with prices 50 percent above their pre-crisis height.

However, those Net Operating Incomes used in the valuations are unlikely to remain at their historic highs as COVID-19 weights into the equation. Today, small businesses face distancing restrictions and new seating capacity issues, all of which are sure to compress NOI for future valuations. Simply put, if income drops by, say, half, real estate valuations across the country are in real big trouble.

Implications for Today

When I look back in time to the farm crisis of the 1980s, one of the primary issues the farmers faced was the high debt vs. the property value they were carrying on their farms, in short, the cost of facilities. When annual incomes dropped from the high in 1973 of $92 Billion to just $8 Billion in 1983, the farmers just were unable to make their debt payments.

Today, according to the SBA, there are about 30 million small businesses that employ about half of the workforce. Typically the largest operating expense (other than labor) is facilities’ cost, either through debt payments or rents. Both have skyrocketed in the past decade, similar to their housing costs.

My concern is that like the farmers of the 1980s, today’s small businesses will likewise be unable to recover their pre-COVID revenues and, in turn, like the farmers of the 1980s, be unable to make the payments on their facilities.

In short, today, the cost of commercial space is just too damn high, and left to its own devices will not likely change— the problem is not going to fix itself. The result? Farm property values plummeted, and in the end, large Wall Street Investors and corporate farms swooped in and picked up properties for pennies on the dollar.

During the 1980s, Congress failed to take any meaningful action to stabilize farm property values. The result? Nearly twenty-five percent of all farm assets were lost, and the number of farmers dropped from 6.8 million to only 2.2 million by the end of the crisis. The farm crisis brought about profound social, political, and economic reforms in the agricultural sector.

Suppose we as a country fail to take any meaningful action to fix the problem of overly high real estate values. In that case, small business may likely suffer the same consequences as the 1980s farming industry. The industry incurred a 97% drop in participants—equating to a possible loss of 29 million small businesses, and nearly half of the workforce will be unemployed.

The time has come for Congress to take big action to keep this from repeating the 1980s catastrophic results.

We cannot leave this process to chance.