Background:

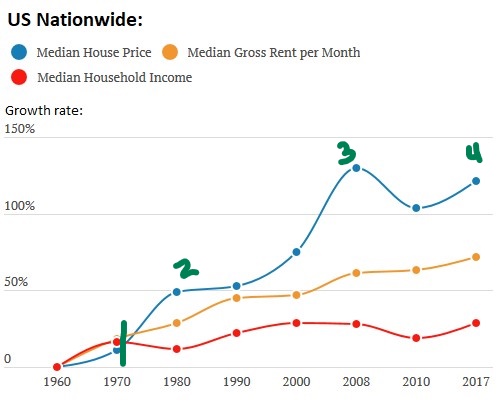

After the financial crashes in 1929, the Roosevelt Administration established the process of financing our homes through the New Deal. Before this, the Federal Government played no role in our housing. During this period (1930 to 1972), homeownership reached an all-time high and was very affordable. However, at inflection point 1, (below) the Nixon administration changed the financing rules and put the responsibility back into private enterprises’ hands. Inflection points 2 and 3 represent the housing market crashes of the 1990s and 2008. In this blog, we will discuss the housing crashes and their causes. At inflection point 4, we discuss the current impending housing crash and its most likely causes–Risk vs. Moral Hazzard.

Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS)

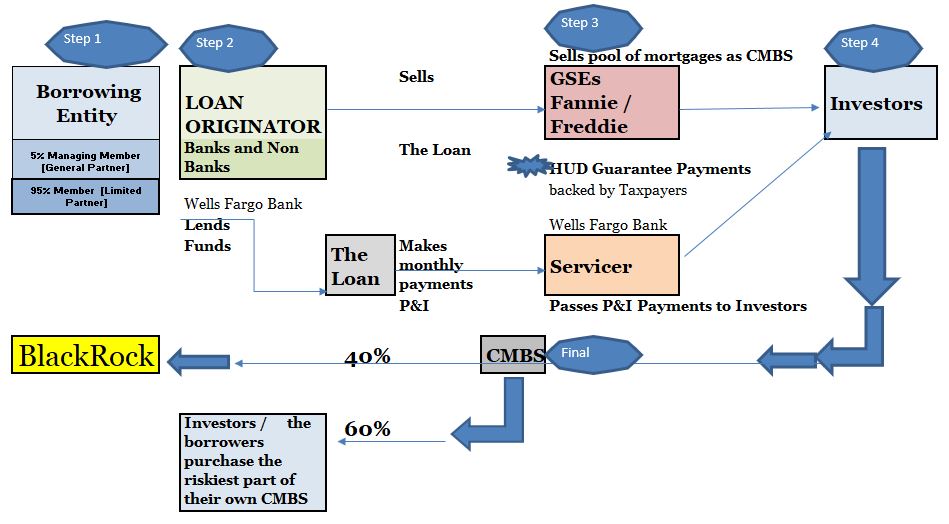

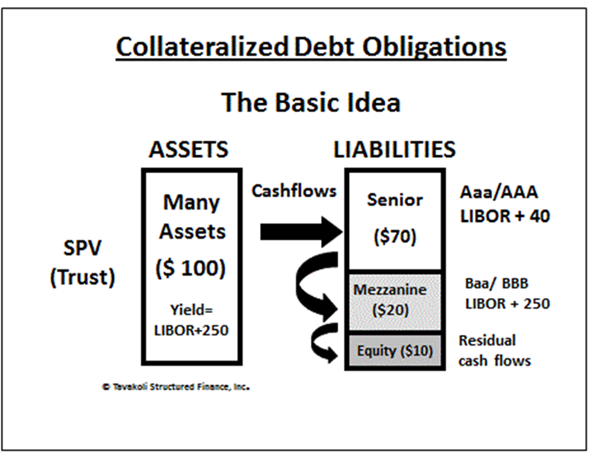

CMBS are investments secured by a pool of commercial mortgage loans held in trust for investors’ benefit. The investors buy certificates with different seniorities entitling them to receive the cash flows from those pools of mortgage loans, see Figure 5.

Most mortgage-backed securities are issued by the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation and U.S. Government-Sponsored Enterprises (GSEs). They bring capital to the housing and multifamily markets. GSE’s roles are critical in providing liquidity, affordability, and stability to the commercial and residential mortgage markets. This report examines how CMBS is used to finance these properties and how it affects the taxpayers who guarantee those debts.

The first MBS type markets began in the early 1990s when the Resolution Trust Corporation issued CMBS to liquidate the bulk sales of commercial mortgage pools inherited from the defunct savings and loan industry. By 1993, Wall Street investment banks set up originating offices in association with mortgage bankers. Bankers began taking on massive risks in the MBS market. By the end of the 90s, a bailout package was bequeathed to the taxpayers in an amount greater than $132 billion—at the heart of the issue, they began to use new synthetic security with fractional ownership.1

Then, before the Financial Crash of 2008, lenders would originate residential loans and quickly resell them to investors in the form of (Residential) RMBS, allowing those lenders to pass the risk onto investors. Regulators argued that Wall Street institutions with strong incentives to protect shareholders would regulate themselves by carefully managing their own risks.2

Lenders and Wall Street Banks earn massive fees for originating and selling those loans, per Figure 7. However, in the end, Vincent Reinhart, a former director of the Federal Reserve, told theFinancial Crisis Inquiry Commission (FCIC) that he and other regulators failed to appreciate the complexity of the new financial instruments, i.e.,–Structured Securities.3 In 2008, the taxpayers provided $191 Billion in bailouts to the GSEs (HUD entities) 4 The Federal Reserve gave BlackRock no-bid contracts to manage the toxic RMBS, assets. Total toxic bond purchases reached $4.5 trillion by October 2014. It sits at $8.5 trillion now, the effect of a 131 percent increase.5

Today, there is more government-backed housing debt than at any other point in U.S. history—33% more than in 2008. Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Housing Administration guarantee almost $7 trillion in mortgage-related debt.6

But what is behind those loans and offsetting bonds? How solid are they? The 2008 Great Recession saw nearly 30 percent of the multifamily CMBS and Collateralized Loan Obligations (CLO) end in default, and the entire multifamily housing sector suffered catastrophic losses.

A key factor contributing to the 2008 financial crisis was the rapid decline of the U.S. housing market, which exposed weaknesses in trillions of dollars of mortgage-backed securities. Today, the economy faces a COVID-driven slowdown that many believe will expose similar flaws in the multifamily mortgage-backed securities.

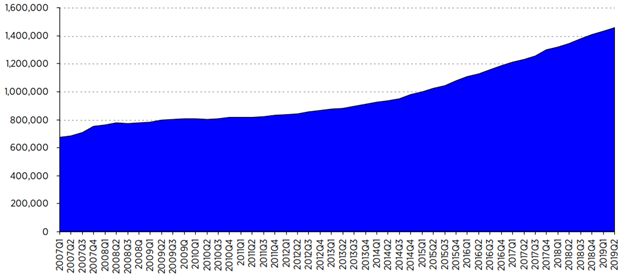

Today, one of the most popular Wall Street investments is the CLO, a single type of security backed by a debt pool. Today they are made up of highly-leveraged multifamily properties and have ballooned to $1.6 trillion per Figure 1. CLOs were typically corporate debt with weak credit ratings or loans taken out by private equity firms to complete leveraged buyouts.

Figure 1. Multifamily Outstanding Securitized Debt ($ millions)

In the end, in both financial crashes—the 1990s and 2008; the collateral valuations supporting those investments were grossly overvalued.

How the MBS Markets Work

A single deal can involve several parties: the general partner (GP), limited partners (LP), contractors, lenders, appraisers, attorneys, and more. However, the first step in becoming an investor in these MBS-type programs is to qualify.

First, you must qualify to participate:

Qualifications to Invest–17 CFR § 230.501 – Definitions and terms used in Regulation D.

Sellers of unregistered securities are only permitted to sell to qualified investors, who are deemed financially sophisticated enough to bear the risks.

- A person must have an annual income above $200,000 ($300,000 for joint income)

- A person shall have a net worth exceeding $1 million, excluding the person’s primary residence.

Figure 2. How the MBS Process Works

Step 1: The Borrowing Entity

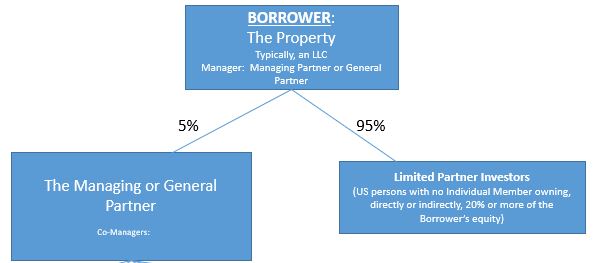

This is how ownerships are typically set up for this type of investment see Figure 3.

a. The Borrowing Entity

The entity that receives money from a lender with the agreement that the money will be repaid. The borrower also owns the collateral or assets of the business. In most MBS relationships, the borrowing structure comprises a General Partner [or managing partner] and limited partners.

b. The General Partner (GP)

The GP manages the limited partnership operations based on terms included in the partnership agreement and has some liability for its debts and obligations.

Principal Sponsor

A sponsor is the management team responsible for all aspects of a commercial real estate project on behalf of the equity investors [limited partners]. The sponsor is often referred to as the GP or Managing Member. The sponsor has essential roles and responsibilities throughout a project’s lifecycle—including sourcing the deal; in many cases, they construct the project, obtain financing, and finalize the process.

How the Sponsors Make Money in the Transaction

• Acquisition Fees, See Figure 7

• Directly invests five or more percent as LPs

• Asset Management fees (Annually)

The General Partners or Sponsors are Creating Risk

For Example, “Greystar Credit Partners maintains a credit strategy that involves acquiring subordinated and securitized debt issued by U.S. Government-sponsored entities. It is a logical progression for us,” Greystar Founder and CEO Bob Faith said in a statement. “Our vertically-integrated rental housing platform, together with our intimate knowledge of the origination and underwriting guidelines utilized by the GSEs, positions us well to invest in the most subordinate part of the capital structure.”7 See Figure 5.

Figure 3. Ownership Structure

c. The Limited Partners (LP)

Limited partners act as silent partners by providing capital, usually a one-time investment. They have no material participation in the business’s operations. Their risk is limited to their investment, and they receive income and capital gains.

Step 2: The Loan

The Lender- Underwriter

The four largest lenders in the market are now nonbank entities. Meaning they are not part of the Federal Reserve’s safety net; in fact, nonbank entities are servicing over 70% of the market. They are unregulated as the HUD entities have no authority or jurisdiction to monitor them. However, they are required to be an approved GSE Delegated Underwriting and Servicing (DUS) Lender. The program grants them the ability to underwrite, close, and sell loans on multifamily properties to the GSEs without prior review of the transaction. These DUS lenders must abide by certain credit and underwriting standards–they are subject to ongoing credit review and monitoring. However, no one is watching to ensure they follow the rules this high-risk industry has been left to self-regulate.

One of the nonbanks’ big modifications in the syndicated loan market is that the arranging bank now aims to distribute as much of the loan as possible to investors and keep very little on their own books. Presently, the arranging banks retain, on average, only about 5 percent of the loan.8 Historically, lenders maintained over 60% of the transaction, referred to as skin in the game.

For example, in recent years, lenders like Wells Fargo have built a thriving business raising capital for nonbank real estate lenders with a newer bundled-loan product. The bank effectively helps finance some of the more aggressive competitors to its commercial real estate lending business. Critically, the newer securitized CLOs is mainly backed by whole loans on unstabilized properties — real estate that is not fully operational or leased. Each securitization typically includes a single lender’s loans, with the lender, not the investment bank, packaging the securitization.9 Meaning, separation of duties and responsibilities meant to provide a backstop to malfeasance no longer exists. Once again, no one is watching the process; there is no designated regulator.

The Loan Terms

- Non-recourse loans, which protects the borrower

- Offers a high leverage percentage with an 80% loan to value ratio (LTV). Some even offer up to 90% LTV and more with mezzanine financing [regulated banks can only provide 75% LTV].

- Often lower rates than comparable traditional bank loans

- Permit cash-out refinancing

- The ability for an Early Rate Lock up to 12 months forward

- Supplemental financing available one year after closing the first mortgage

The loans are well-liked by commercial real estate investors due to their lax underwriting standards and because they are non-recourse and fully assumable. Most CRE borrowers can access this loan even if they generally do not meet banking standards.

One of the many downsides of CLOs is the highly complex nature of these products. Investors may not know precisely what they are buying or whether the package is worth the stated value.

For Example, on May 09, 2019, an investing group sued JPMorgan Chase and other Wall Street banks over a loan that went sour in 2014. They alleged that the underwriters engaged in securities fraud. The suit stems from a $1.8 billion loan that J.P. Morgan arranged for Millennium Health LLC. However, within a short period, investors saw the value of their loan plunge. The company disclosed that federal authorities were investigating their billing practices. In the end, J.P. Morgan was found to be fully aware of the investigation. Still, they failed to disclose the weaknesses with the investors adequately. 10

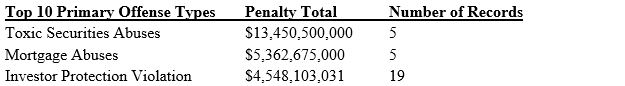

The participating banks have a long history of maleficence. For example, JP Morgan Chase, per Figure 4, lists the 29 times the lender has been caught in bad faith acts in the derivatives markets.

Figure 4. JPMorgan Chase reported penalties for violations of law

Today, the lenders tout once again that their new securitized CLO products are rock solid and good for the housing markets. But we must ask the question, after the two earlier failed attempts in the 1990s and 2008, are the CLOs really safe? To answer this question, we will look at four loan closings and report on our findings.

The Loan Supporting the Investments found to be High-Risk

We completed a study to determine whether the GSEs administer Fannie and Freddie underwriting programs per their regulations, policies, and procedures. More specifically, we monitored and reviewed the closing of four multifamily projects to determine whether the lenders (risk sharers) sourcing and closing those loans are meeting their lender requirements and the GSEs’ underwriting standards.

The Infrastructure Study [not detailed in this paper] concluded that the lender is reporting less than 20 percent of infrastructure repair costs. They are leaving massive costs unaccounted for and the quality of life for the tenants as substandard and, in many cases, dangerous.

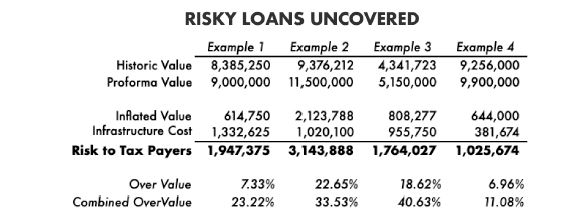

Per Table 1, the historical value (HV) is established on the date of the appraisal by a certified and HUD-approved appraiser. The pro forma value (PV) assigns a higher value based on future rent increases. The inflated value (IV) is that portion of the value assigned to future rent increases (Table 1, below). Therefore, the taxpayer’s risk is the inflated portion of the appraisal and the infrastructure costs (IC). We also reported that the rent increases are not sustainable, see the book, Stealing Home for more details.

Table 1. Risky Loans Uncovered

The risk (R) equals the (IV) plus the (IC), which is the amount of projected collateral shortfall should the property be taken back in default. This loss is then charged to the American taxpayer as the Treasury issues bonds backing those losses; the projected combined loan losses range from a low of 11.08 percent to a high of 40.64 percent.

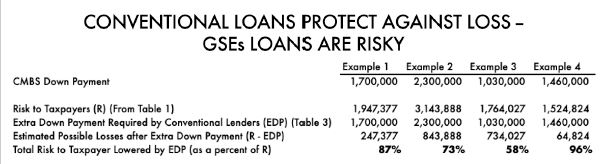

Regulated Conventional Banking Loans Protect Against Loss, but GSE Loans Are RISKY

In today’s commercial lending world, the community banking system (under $10 billion) maintains more robust credit policy standards, such as bigger down payments requirements. The amount of required down payment can, as we will see, protect the taxpayer from excessive financial bailouts.

When we carry the risk (R) to the taxpayer from Table 1 and looking at the additional required down payment (EDP) on conventional loans, the additional down payment is the requirement by federal banking policy. The traditional lenders are protecting their investments with stricter lending guidelines. In contrast, GSEs are offering the best rates and terms to the riskiest of borrowers and lenders.

Table 2. Conventional Loans Protect Against Loss

This can be seen by revealing the dollar risk (R) to the taxpayers and then matching the additional down payment (EDP) required by commercial banks. The final loss results (R – EDP) yield the final estimated loss results. As we see in Table 2, traditional lenders take more exceptional care to protect their investment in the loans. In fact, the study shows that commercial banks’ loan losses are projected to be between 58 to 96 percent lower than the GSEs’ projected loan losses.

Other CMBS/CLO Collateral Valuation Issues:

- Loan Size and Complexity has more than Doubled Since 2008

The median issue amount of CMBS sold since 2015 was $523 million, while the median deal size in 2009 was $247 million, an increase in size and complexity of approximately 111.7 percent.11

- CMBS Loans Found to be Over Valued

During 2020, as more and more CMBS borrowers affected by the COVID-19 Pandemic began defaulting on their payments, those properties ended up in special servicing. According to Wells Fargo data reported by the Financial Times, the appraisals on those properties had averaged a 27% drop in value.

“The numbers themselves are atrocious,” PineBridge Investments portfolio manager Gunter Seeger told FT. “A [nearly] 30% markdown in appraisals pretty much across the board is horrific.”12

- Wells Fargo and Other Large Lenders caught in Market Manipulation Scheme to inflate CMBS/CLO Appraisal Values

A 2019 whistleblower complaint submitted to the Securities and Exchange Commission alleged that some DUS Lenders — including Wells Fargo, have engaged in systematic fraud. The fraudulent practice allowed the banks to award larger loans than the borrowers were qualified or could repay. Securities that contain loans for properties like hotels, multifamily, and office buildings have inflated profits, the whistleblower claims. 13

Our study concluded that if CMBS is inaccurately rated or dishonestly represented, it can present the same uncompensated risks to buyers as the fateful sub-prime RMBS of 2008.

Nevertheless, there are no rules or regulations for standardizing MBS structures or the collateral; therefore, their valuations can be difficult and unpredictable.

Step 3- The loan is Packaged and Sold to Investors

The originating lender funds mortgages that conform to the GSE underwriting standards, then pooled together, securitized (i.e., converted into mortgage-backed security bonds), and sold to investors. With the government’s guarantee of timely payment of principal and interest, it can be sold to investors and traded in the secondary market.

Figure 5. The Collateralized Debt Obligations

The Loan Servicer

After the lender issues the borrower a loan, all their future dealings occur with a commercial mortgage servicer, called a master servicer. The master servicer collects all future MBS loan payments. Nevertheless, should the borrower fail to make the payments due on their loan, then a “special servicer” is assigned to work with the borrower to make changes to the terms or fees of their loan. These steps may include foreclosure proceedings.

Step 4 Who are the Investors?

Today, multifamily real estate has become a core component of the ultra-high net worth portfolio, essentially making the industry the new investment of choice for the wealthy and elite. This group is known for its demand for maximum profits.14

What’s New This Time?

The New Fractionalized Ownership Structured Financial Securities and their Risk Explained

What are Structured Transaction Products?

There are basically two types of fractional real estate ownership: Delaware Statutory Trust (DST) and Tenant-In-Common (TIC) ownership. Each option has become increasingly popular as an alternative investment over the past decade. Fractional ownership is a phrase that defines direct property investment as a percentage share rather than buying the whole property. It grants many unrelated parties ownership of a real property asset and shares in rents collected and earnings from appreciation once a property is sold. The mortgage-related assets serving as collateral are structured into separately traded securities called classes from AAA to Mezzanine. Subordination refers to a structure in which each class or tranche of certificates has a different right to the cash flow of payments and the allocation of losses. Senior tranches are given the first claim on cash flows and the last position concerning losses per Figure 5.

How Safe are these Products?

FNMY Mae Warning: Investors should exercise care to understand the value of any mortgage-backed investment fully and diligently review the applicable disclosure documents. Mezzanine and subordinate certificates are backed by the same pool of loans as the senior certificates are but without Freddie Mac’s guarantee. The bottom or riskiest 15 percent of the transaction is the unguaranteed mezzanine and subordinate certificates. However, they account for the vast majority of the risk. Investors in the unguaranteed certificates are the last to receive a payout and the first to take any loss.

What’s the Difference Between Fractional Ownership vs. REIT Investment?

Upon investment in an equity REIT (real estate investment trust), you acquire ownership in several different income-producing properties that are all in one asset class. The investors then share the rental income. Investors cannot dictate what properties the REIT will buy or what capital improvements might be made, or when the property might be sold. However, selling your REIT investment is not complicated and is traded daily through the stock market. However, selling the Fractional ownership is much more restricted and is not sold through Wall Street but through private transactions between the limited partners and approved by the managing partners. Therefore, selling fractional ownership is slow and complicated.

How to Become a Limited Partner Investor

a. The Subscription Agreement

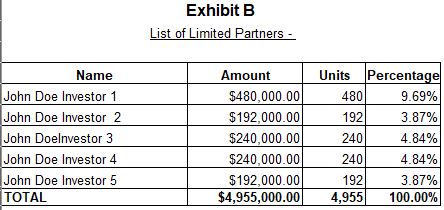

In an LP, a GP brings in limited partners using a subscription agreement. A subscription agreement contains the investor’s application to join and the terms of the arrangement. It provides a two-way guarantee between the company and the subscriber. In this example, John Doe Investor 1 has invested $480,000 for 480 Units and will have a 9.69% ownership in the property investment. Total Investment of $4,955,000 with 4,995 Units totaling 100%.

Figure 6. Exhibit B- List of Limited Partners

b. The Limited Partnership Agreement

In the process, the LPs grant complete control of the property and investments to the General or Managing Partners.

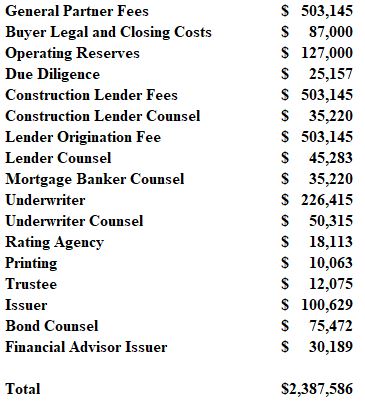

However, most of the L.P.’s investment will be absorbed in covering the cost of putting the transaction together–the massive fees. In this example, Figure 7, The $50 million construction to perm loan is secured by a 266 unit apartment high-rise facility, and the fees to complete the project are estimated at $2,387,586. Fees have become a core income-generating facility for Wall Street.

Figure 7. Transaction Costs- The Massive Fees

To understand the sheer volume of fees this process generates, we focus on Greystar Credit Partners’ growth strategies. For example, they complete over 2,000 such deals annually,15 that’s $4.8 billion in fee generation by one company.

Step 5 Servicing Leasing / Management Maintenance of the Investment and Properties

In Figure 2, using Greystar’s strategy, the final step outlines the 60 / 40 split in the bond placement. Greystar holds the riskiest bonds for their investors and sells the 40 % highest-rated bonds to BlackRock.

The complex fractionalized ownership structures now dominating the housing markets may prove to be the markets undoing, similar to the residential loans’ fate leading up to the 2008 Financial Crash.

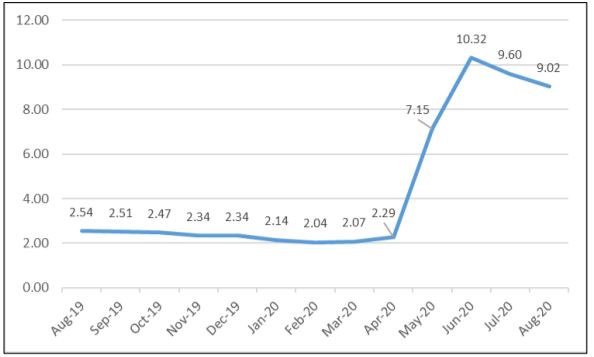

In June 2020, CMBS delinquency rates hit almost peak levels, with 10.32% over 30 days past due. This is near the previous peak of 10.34% in 2012. As shown in Figure 8, the rate fell in July and August to 9.02% but remains considerably higher than the pre-pandemic level. These elevated levels are driven by delinquencies in lodging (22.96%) and retail (14.88%).16

As a matter of reference, in a normal market setting, delinquencies typically remain below 1.15%. In 2008, for example, the delinquency rate on home mortgage loans hit 4.25% and led to catastrophic losses in the housing industry; over 10 million Americans lost their homes.

What happens to the Losses?

Figure 8. Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities (CMBS) Delinquency Rates Sept. 2020

“When you have a big loss in the marketplace, there are only three people that can take the loss—the bondholders, the investor, or the taxpayers,” said William Seidman. He led the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) from 1989 to 1991. “That’s the dance we see right now. Are we going to shove this loss into the hands of the taxpayers?” 17

The Risks

The tax-credit syndicators capable of generating the institutional investor-owned properties are forming complex, fractional ownership-style structures. In November 2018, Julie Segal reported in the Institutional Investor that J. P. Morgan had issued a new study for the firm’s wealthiest clients, warning that those assets may be hard to sell once the economy goes south. That’s because the larger, more sophisticated investors will likely have more private assets [Fractional Ownerships] in their portfolios that are hard to sell. “The conventional wisdom is that if you are big and sophisticated, you’ll be okay,” said John Bilton, head of global multi-asset strategy at J. P. Morgan Asset Management. “But the reverse is true.”18

Fractionalized Ownership Properties are Difficult to Unwind

For example, several years ago, as a loan broker, I was called on to unwind one of these transactions, it was small, yet it took over three years. The Appraiser was quoted:

Figure 9. The Appraiser noted the Time Delay

The subject’s owners xxxxxxxxxxx have agreed to sell the appraised property to xxxxxxxxxxxxxx. The parties are currently in escrow. This is an arm’s length transaction and a cash-equivalent sale. The subject’s buyer intends to operate the property as an apartment building, which was its original use. There were reportedly about 440 fractional members, and some of those may be deceased or reside out of the country. Consequently, the process of dissolving the membership has been so slow (three years) that the buyer’s interest has been reassigned twice since escrow was opened.19

One of the primary reasons for the delay in unwinding one of these projects is that all LPs have to sign off on the sale. Those owners who don’t sign the consent to the sale or can’t be located require the GP to initiate a foreclosure proceeding, a time-consuming and expensive process.

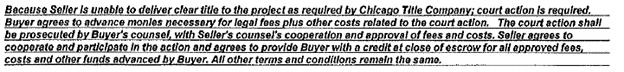

Figure 10. Those Fractional Owners Difficult to Reach- The Title Company Handles the Foreclosure Process

Furthermore, when these Synthetic CLO transactions fail to perform, the limited partner investors have few options to protect their investments. Many turn to the courts for assistance; these cases can drag on for years and create massive operational and liquidation roadblocks for the Managing Partners, for example, in the case of Monogram Residential:

Figure 11. Limited Partners Sue for Redress

Time and again, including the financial crash of the 1990s and 2008, these types of synthetic investment vehicles pose a significant risk to the housing markets. However, the big unanswered question remains, when the markets head south, what will happen when these types of securities begin defaulting on their payments. What will happen to the tenants who live in these properties? What will happen to the housing in the areas where a significant percentage of housing is placed into financial limbo? Are cities prepared for this crisis?

The Taxpayers

Asset managers and institutional investors, before the COVID-19 Pandemic, have been raising concerns about what will happen during the next period of extreme market stress. Once again, as in 2008, once the crisis begins and vacancies begin to escalate, those bonds will once again fail in their value.

Currently, the GSEs have the most liberal lending standards within the industry, with minimal oversight. The borrowers of the loan products do so with double the risk of conventional loans — minimal skin in the game and high leverage. Risk is growing exponentially within the financial bubble. HUD’s lax standards, to make matters worse, have the potential to cost the American taxpayer hundreds of billions of dollars in losses should the investors gamble, not pay off.

The 2008 Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission would coin a new phrase known as “moral hazard. “The financial market executives knew their respective governments would never let them go bust—the ensuing chaos would be too high. The most prominent financial institutions began to take excessive risks, knowing that should things go seriously awry, taxpayers would bail them out—they did.21

Regardless of how this plays out, the investors win. The renters and taxpayers are the big losers. The taxpayers are required to pay the guarantee of the investors’ risky investments even though over 90 percent of Americans are prohibited from participating in this type of loan program (can’t meet minimum qualifications). We are paying for a party we will never get to attend.

The tenants work hard jobs for low wages and yet will have taxes withheld from their meager paychecks to fund the wealthy billionaire investors’ guarantees and pay for their gambling habits.

The time has come to begin the conversation on fixing how we finance our homes.

This Blog is a summary from the Economic Study, The New Landlord , a Study on the Three-Part Leasing Strategy, Powered by Big Data, and Artificial Intelligence©

End Notes:

- Jack Willoughby, “The Lessons of the Savings-and-Loan Crisis,” barrons.com, April 13, 2009, https://www.barrons.com/articles/SB123940701204709985?tesla=y

- “The Financial Crisis Inquiry Report: Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States,” Discover Economic History, Federal Reserve, January, 2011, fraser.stlouisfed.org/title/5034

- Ibid.

- “Quarterly Financial Supplement Q3 2019,” Fannie Mae, October, 2019, fanniemae.com /resources/file/ir/pdf/quarterly-annual-results/2019/q32019_financial_supplement.pdf; and, “Freddie Mac Reports Net Income of $1.7 Billion and Comprehensive Income of $1.8 Billion for Third Quarter 2019,” Freddie Mac, October, 2019, freddiemac.com/investors/financials/pdf/2019er-3q19_release.pdf

- David L. Bahnsen, “Did The Financial Crisis End?” National Review, March 2019, nationalreview.com/magazine/2019/03/25/did-the-financial-crisis-end/

- “Housing Finance at a Glance, a Monthly Chartbook,” Housing Finance Policy Center, June, 2018, urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/98669/housing_finance_at_a_glance_a_monthly_chartbook_june_2018_0.pdf

- Jeremiah Johnson, “Greystar Initiates Funding For $500 Million Debt Fund,” Housingwire.com, June, 2018, housingwire.com/articles/43623-greystar-initiates-funding-for-500-million-debt-fund/

- Max Bruche, Frédéric Malherbe, Ralf R Meisenzahl , “From credit risk to pipeline risk: Why loan syndication is a risky business,” Vox, September 2017, voxeu.org/article/why-loan-syndication-risky-business.

- Jake Mooney, “Wells Fargo rides real estate CLO wave as issuance volume swells,” spglobal.com, Feb, 27, 2019, https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/wells-fargo-rides-real-estate-clo-wave-as-issuance-volume-swells-50211799

- Bloomberg Blog, “Investors suing J.P. Morgan may redefine the leveraged loan market,” pionline.com, May 9, 2019, https://www.pionline.com/article/20190509/ONLINE/190509857/investors-suing-j-p-morgan-may-redefine-the-leveraged-loan-market

- Knyazeva, Lin and Park, “Issuance Activity and Interconnectedness in the CMBS Market,” U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, August 2019, https://www.sec.gov/files/DERA_WP_Knyazeva-Lin-Park_IssuanceActivityInterconnectednessCMBS%20.pdf

- Matthew Rothstein, “CMBS Appraisals Show ‘Atrocious’ Value Loss In Hospitality, Retail Real Estate,” Biznow, September 28, 2020, https://www.bisnow.com/national/news/capital-markets/cmbs-appraisals-real-estate-values-crumbling-10612

- Heather Vogell, “Whistleblower: Wall Street Has Engaged in Widespread Manipulation of Mortgage Funds,” ProPublica, May 15, 2020, https://www.propublica.org/article/whistleblower-wall-street-has-engaged-in-widespread-manipulation-of-mortgage-funds

- “Crow Holding Capital,” crowholdings.com, June, 2020, https://www.crowholdings.com/chc

- “Investor Services,” Greystar, accessed November, 2019, https://www.greystar.com/investor-services/investment-management

- Trepp, CMBS Delinquency Rate Continues Retreat from Near All-Time High, September 2020, at https://info.trepp.com/hubfs/Trepp%20August%202020%20CMBS%20Delinquency%20Report.pdf

- Jon Hilsenrath, Serena Ng and Damian Paletta, “Worst Crisis Since ‘30s, With No End In Sight,” The Wall Street Journal, September 2008, wsj.com/articles /SB122169431617549947.

- Julie Segal, “Large Investors Will Be the Most At Risk in the Next Bond Sell-Off,” Institutional Investor, November 2018, institutionalinvestor.com/article /b1c0x7kq08z5fs/Large-Investors-Will-Be-the-Most-At-Risk-in-the-Next-Bond-Sell-Off

- Appraisal on Real Property, Conversion from Time-Share to Apartment Property. Michael R. Peters, MAI, MBA Managing Partner, Founder California Cert. No. AG001944

- Bradley Hertz, individually and on behalf of all others similarly situated, Plaintiff, v. Monogram Residential Trust, Inc., Mark T. Alfieri, David Fitch, Tammy Jones, etal, Defendants, Case 1:17-cv-02202-GLR Document 1 Filed 08/04/17, https://securities.stanford.edu/filings-documents/1062/MRTI00_01/201784_f01c_17CV02202.pdf

- Ian Goldin and Chris Kutarna, “Risk and Complexity,” International Monetary Fund Finance & Development, September 2017, Vol. 54, No. 3, https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/2017/09/goldin.htm